3S is the abbreviation for “Seiwa Scholars Society,” which consists of the past and current Inamori Research Grant recipients. The 3S has evolved since 1997 with the hope that the interactions among the various specialties of the 3S members can lead to the further development of the research of their own. In the series “Visiting 3S Researchers,” we interview researchers in 3S who are very active in a variety of fields. The 11th interview is with Dr. Akiko Miyamoto (2017 Inamori Research Grant Recipient) from Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts.

Highly acclaimed both in Japan and internationally, the films of Yasujiro Ozu, one of Japan’s most iconic film directors, comprise an oeuvre that has influenced a myriad of filmmakers and creators. Today, however, more than 60 years after the release of his final directorial work, Sanma no aji (An Autumn Afternoon, 1962), there exists a growing number of people who, although familiar with Ozu’s name, have never seen his films.

Dr. Akiko Miyamoto, an associate professor of film studies at Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts, admits that her fascination with Ozu’s films didn’t develop until her university years. So, what ignited her research interest in the acclaimed director’s works?

We sat down for an in-depth conversation with Dr. Miyamoto about the allure of Ozu’s film and the intriguing endeavor of interpreting films through archival resources.

“I Want to Decipher the Eloquent Stories That Film-related Materials Have to Tell Us.”

──How did you first encounter Ozu’s films?

Dr. Miyamoto (title omitted below) I think I first saw one on TV when I was in high school. At the time, I just felt it was a peculiar film, but it didn’t really catch my interest. It wasn’t until I entered university that I started to take notice. In class, we watched Akibiyori (Late Autumn, 1960). There was a scene in the film where three men were sharing a laugh, and the way the alcohol bottles were arranged made them seem to mirror the characters. This composition fascinated me, and I felt myself drawn in by the beauty of the framing.

Later, when I had the opportunity to see the director’s storyboards, I was enchanted by the meticulously documented records. I began to understand that this is how framing and filming methods were decided. I also found a postcard that Ozu had sent to a friend’s child, which was inscribed with gentle words and a picture he had privately drawn. Engaging with such materials made me increasingly intrigued by Yasujiro Ozu as an individual, and I found myself wondering what kind of person he really was.

Once I started watching Ozu’s films with a focus on the director’s conscious intentions, the meticulously crafted compositions—which could be described as overly coherent—became more captivating. From there, I found myself wanting to learn more.

──Ozu has many fans both in Japan and internationally. What were your feelings about conducting research on such a renowned director?

Miyamoto When I began my research, there was already a lot of discourse around Ozu, and the prevailing opinion was that there probably weren’t any new discoveries to be made. Initially, my primary focus was on literary research. Surrounded by so many people specializing in film studies, I wondered . . . is there anything left for me to do? I remember grappling with this doubt.

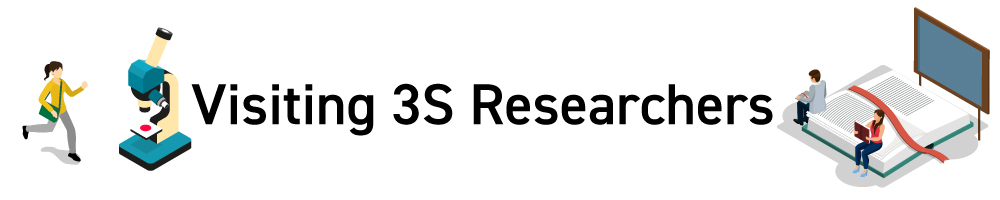

The thing that changed my uncertainty into surprise and delight was finding a script for the film Soshun (Early Spring, 1956) marked up with notations in blue pencil. I was thrilled at the prospect of unraveling the mystery of who had written them and why.

Before encountering this material, I was grappling alone with how to articulate Ozu’s films and wondering who would be interested in what I had to say. However, when I finally had the script for Soshun in front of my eyes, it felt like I’d suddenly been illuminated by a ray of light. It struck me that maybe I should be having a dialogue with the material itself. Whose handwriting is this? Why were these notes made? What exactly happened here? Imagining such things and comparing the script with other materials, it felt like I was starting my research by having conversations with unseen interlocutors.

──What insights have emerged from your study of the materials?

Miyamoto Back then, the prevailing view was that Ozu wouldn’t alter the finalized screenplay for a film once shooting began. However, as I examined screenplays, the diaries of associates, production records, and other materials, it became apparent that such generalizations couldn’t hold. For example, one screenplay had notes indicating numerous alterations had been made on set. Comparing and contrasting multiple copies of scripts that belonged to Ozu and other members of his staff, it became evident to me that changes were being made both during and even after shooting.

──What kind of materials are you currently researching?

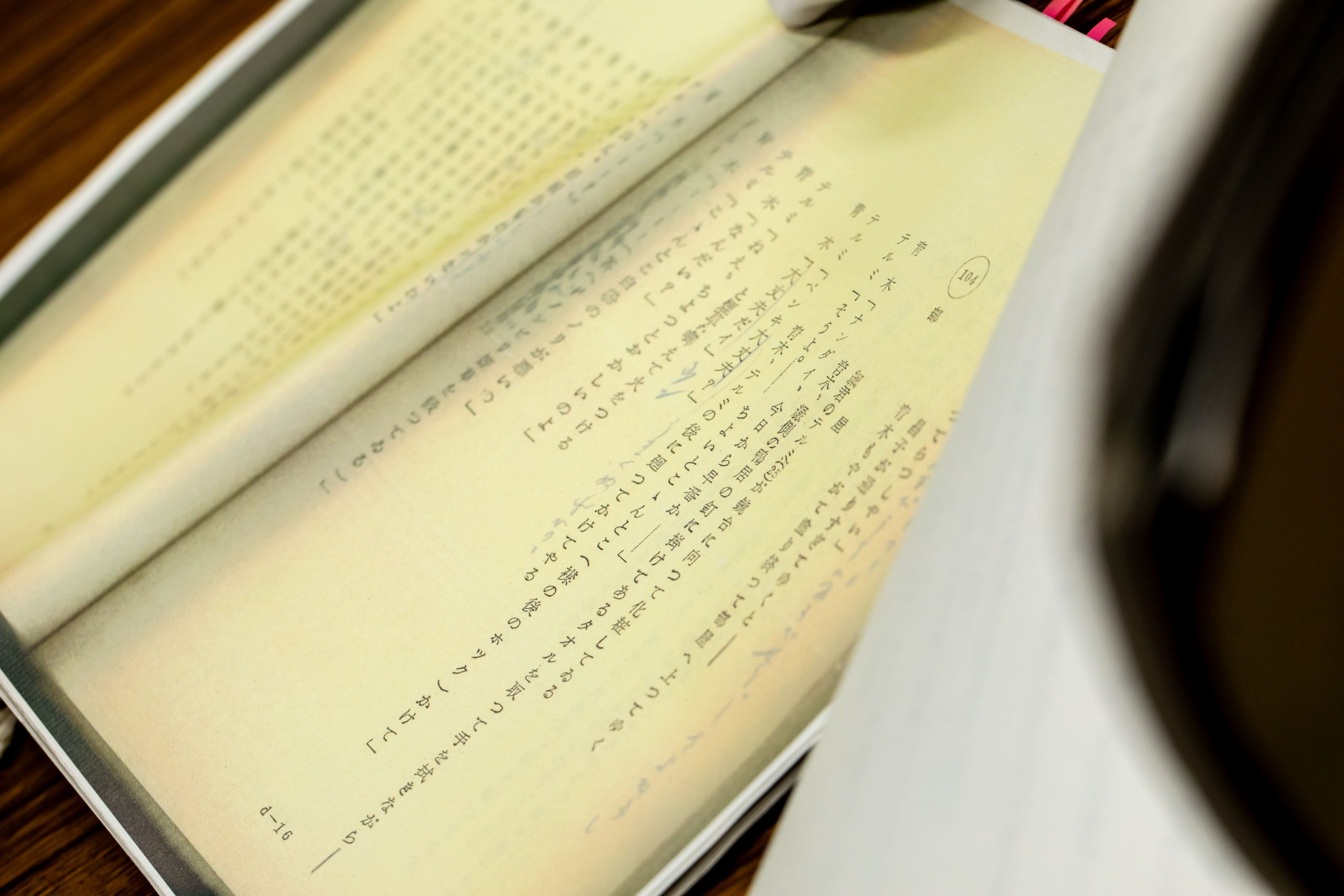

Miyamoto I’m currently in the process of transcribing the diaries of Kogo Noda. Noda was a screenwriter who wrote scripts for Ozu’s films, beginning with his first directorial work. The diaries are written in various notebooks, including ones of about 4 by 6 inches, with meticulous records related to film production written in tiny characters. I’m carefully reading and transcribing each letter. I hope to complete this project within the next 10 years.

──With so many minute characters and faint, hard-to-distinguish sections, deciphering the diaries seems quite a challenging task.

Miyamoto It certainly is challenging. However, I enjoy deciphering handwriting and conducting investigations, so the joy outweighs the hardship. Nonetheless, to avoid distortion of facts due to biased interpretation, I make it a point to revisit the texts after a break. Reading without preconceived notions is crucial in conducting research, I believe.

Honoring and Passing On an Entrusted Legacy

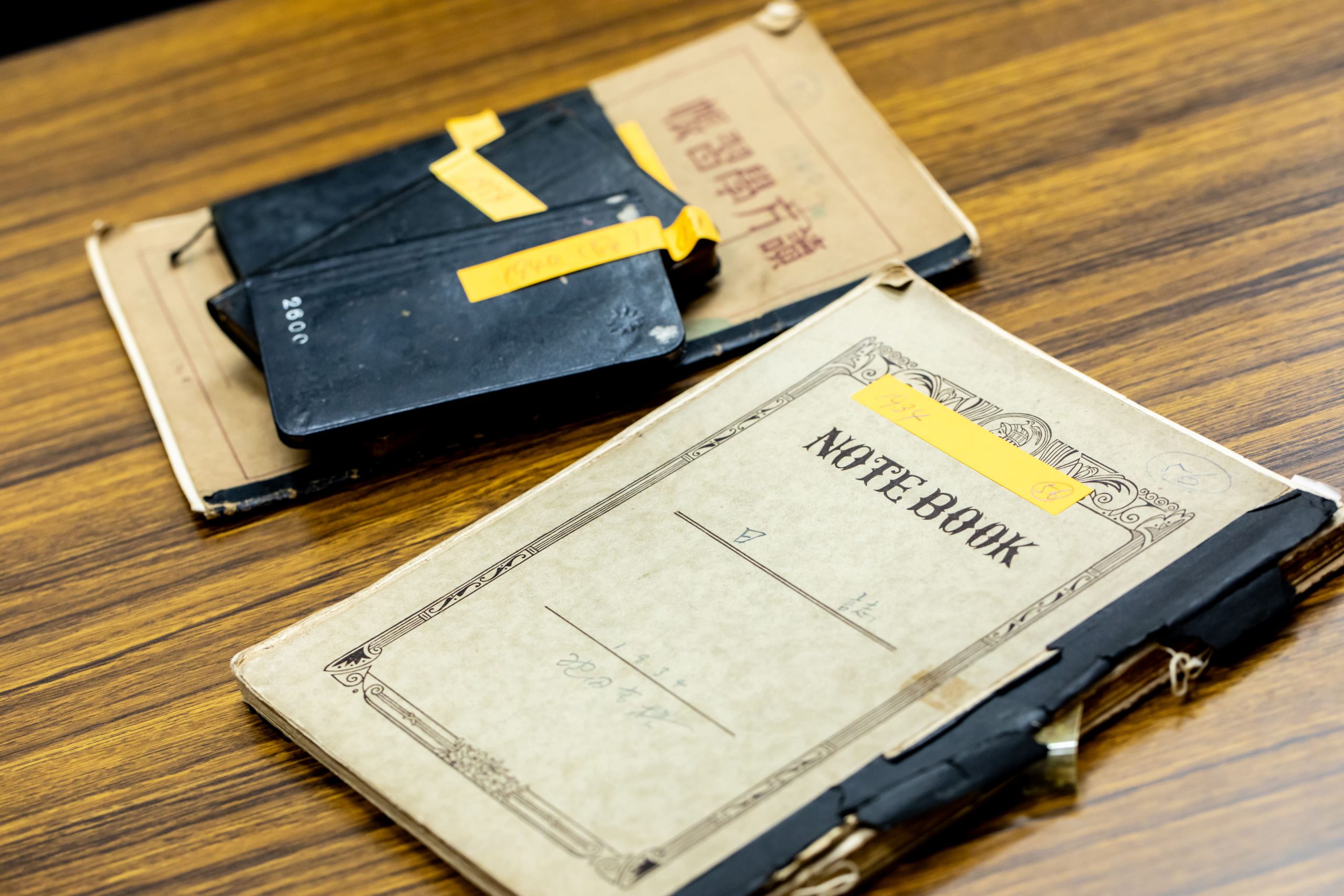

──In 2019, you published Ozu Yasujiro taizen (translated title: The Complete Book of Ozu Yasujiro) together with your co-researcher Kanji Matsuura.

Miyamoto Yes, that’s right. Through correspondence and in-person visits, we were able to hear about Ozu from many people, including producers, cinematographers, and actors who worked with Ozu, as well as directors and musicians who are active today.

We heard some truly invaluable stories, several from people who are now quite elderly. The testimonies and records from the film shoots, I felt, need to be properly preserved and passed on, or else they will disappear. There was a time when I was wondering what I could do as a researcher, but now I feel a strong desire to learn from materials and interviews, and pass on what I’ve learned.

──I understand that you and Mr. Matsuura operate the Ozu Yasujiro Institute.

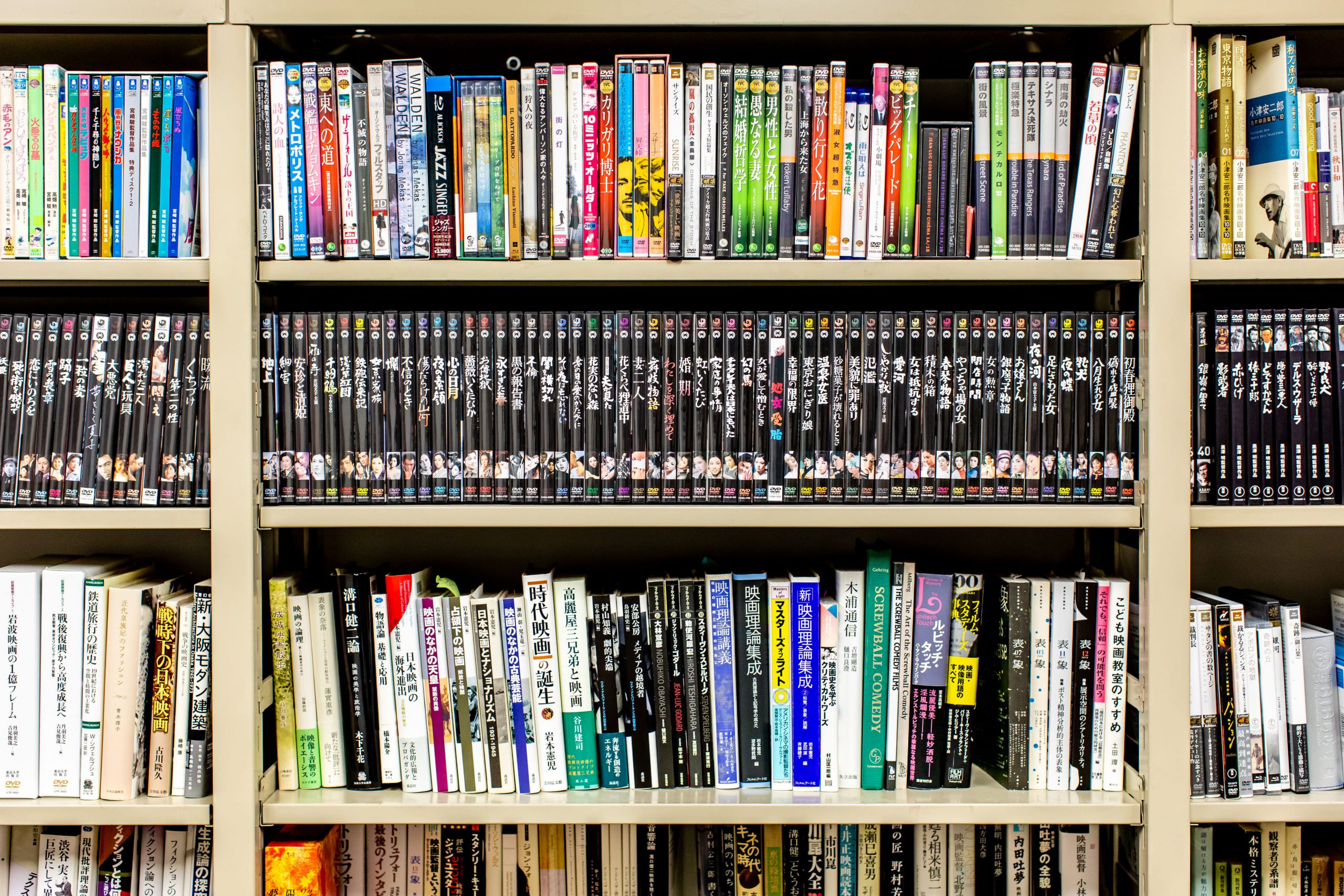

Miyamoto When it comes to Yasujiro Ozu, most of the existing research and critiques have focused on analyzing his completed films. Meanwhile, research on the filming process itself is lacking. We run the institute with the desire to further this kind of research and to create a platform where we can share our findings with a broader audience, not just within the research community.

It was the same with me, but many young people not yet familiar with Ozu tend to find his films difficult and hard to get into. We want to create a space for dispelling this image. We’re featuring some of the interview articles included in Ozu Yasujiro taizen on the Institute’s website,* especially ones we think younger people would enjoy.

── I was particularly interested in the interview with Naoki Urasawa, the manga artist known for works like Yawara! and Monster, discussing the relationship between Ozu’s films and manga.

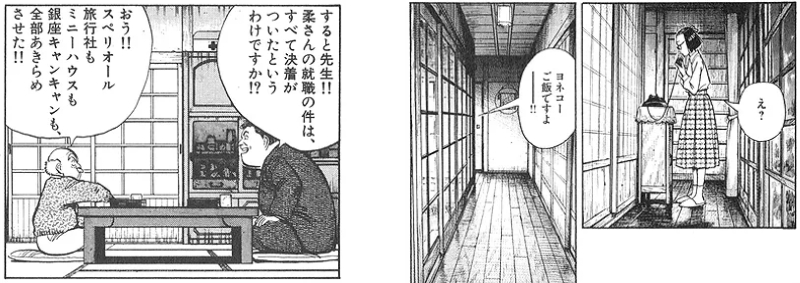

Miyamoto To hear him talk, it seems he watches Ozu’s films more than we researchers do. He watches them with a keen eye for compositions and character portrayals. Elements reminiscent of Ozu’s films are incorporated into his manga, as well. For example, a scene in Yawara! where the characters Jigoro Inokuma and the judo coach Yutenji are talking (see image on the left below) mirrors a composition often appearing in Ozu’s films, where the top surface of a table is barely visible. Additionally, a scene in Asadora! where the character Yone-chan is talking on the phone at home pays a conscious homage to a scene from Ozu’s 1952 film, Ochazuke no aji (The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice) (see image on the right below).

──What kind of activities are planned for the Institute in the future?

Miyamoto We are planning lectures and events. The year 2023 marks the 120th anniversary of Ozu’s birth, and we’ve been blessed with the opportunity to introduce his films at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in the United States. We’d love to use this opportunity to convey the fresh appeal of Ozu’s films to a large audience.

The Mysterious Phantom Allure of Film

──Where do you think the allure of film research lies?

Miyamoto Films are perceived, interpreted, and enjoyed differently by each person who watches them. When we delve into the production process, learning about the people involved and the society at that time, it really alters the way we see the work. When I ponder the nature of a film, it feels like something of a phantom, something that you can’t easily pin down or describe in a single word or phrase. It’s a bit frightening, but it makes you want to delve deeper and know more.

The film world is a real nexus of different people—creators, performers, deliverers, and viewers. This really brings a level of complexity to research; it’s not straightforward. It needs to be explored from all sorts of angles. But this is exactly why it’s so rewarding.

For most people, when they watch a film, the first thing they’re drawn to is probably the story. But there are other things we can pay attention to, like the music in a scene or the demeanor of the people. Just like how I, as a university student, had a sudden epiphany that changed my perspective while watching one of Ozu’s films, I think everyone has their own way of seeing and enjoying films.

Sometimes, I watch Ozu’s films in class with my students. They are 18 or 19 years old, living in an era very different from the setting of the films, but their unique perspective has yielded some interesting discoveries. For instance, some have mentioned that Ozu’s clean compositions are similar to what they see on Instagram or that although they find the way lines are delivered to be strange at first, it soon grows on them. Even with films I’ve watched countless times, watching with the students always brings new discoveries, and I find that immensely enjoyable.

Why I Wrote, “The Study of Yasujiro Ozu Has Just Begun.”

──Would you be interested in collaborating with researchers from other fields?

Miyamoto Absolutely, I’m keen to. I wonder what would happen if we quantified the charm of Ozu’s films, the allure that is so hard to express in words. For example, characteristics of dialogue, rhythm, pitch, and so on.

There’s also this notion that characters in Ozu’s films seldom change their expressions. On the other hand, some characters have such rich expressions. I fantasize about working with a cognitive psychologist to contemplate the effects this has. The soundtrack and the direction are also considered “peculiar.” For instance, cheerful music is used to accompany a sad scene. I’d like to explore how these features and this kind of direction influence people’s emotions. I also wonder how experts in architecture would perceive his unique compositions and the features of the houses depicted in the films.

──I was particularly struck by this statement on the Ozu Yasujiro Institute website: “The study of Yasujiro Ozu has just begun.”

Miyamoto Plenty of analyses have been conducted on Ozu’s films, but studies of the production process are still lacking. It was with this in mind that I intentionally used the words “just begun.” Of course, I feel immense gratitude and respect for the body of knowledge and insight that has been built up by scholars who have engaged in research on Yasujiro Ozu and criticism of his films, and it’s thanks to this foundational work that the field is where it is today. I want to move beyond that and conduct new research as well. It was with this resolve that I wrote those words.

In truth, there are moments when a hint of fear crosses my mind, tempting me to erase that sentence (laughs). However, I’ve come to realize that I want to be sincere in engaging with the materials, people involved in the films, and Ozu as an object of study together with my research colleagues. I want to advance the research, drawing on methodologies that have been used in film studies and history.

I hope that young people who have never encountered Yasujiro Ozu might think that if the field has “just begun,” then they will try it, too. That would also make me happy.

──Thank you very much.

*The Ozu Yasujiro Institute’s website(Japanese only):https://www.ozuyasujiro.jp/

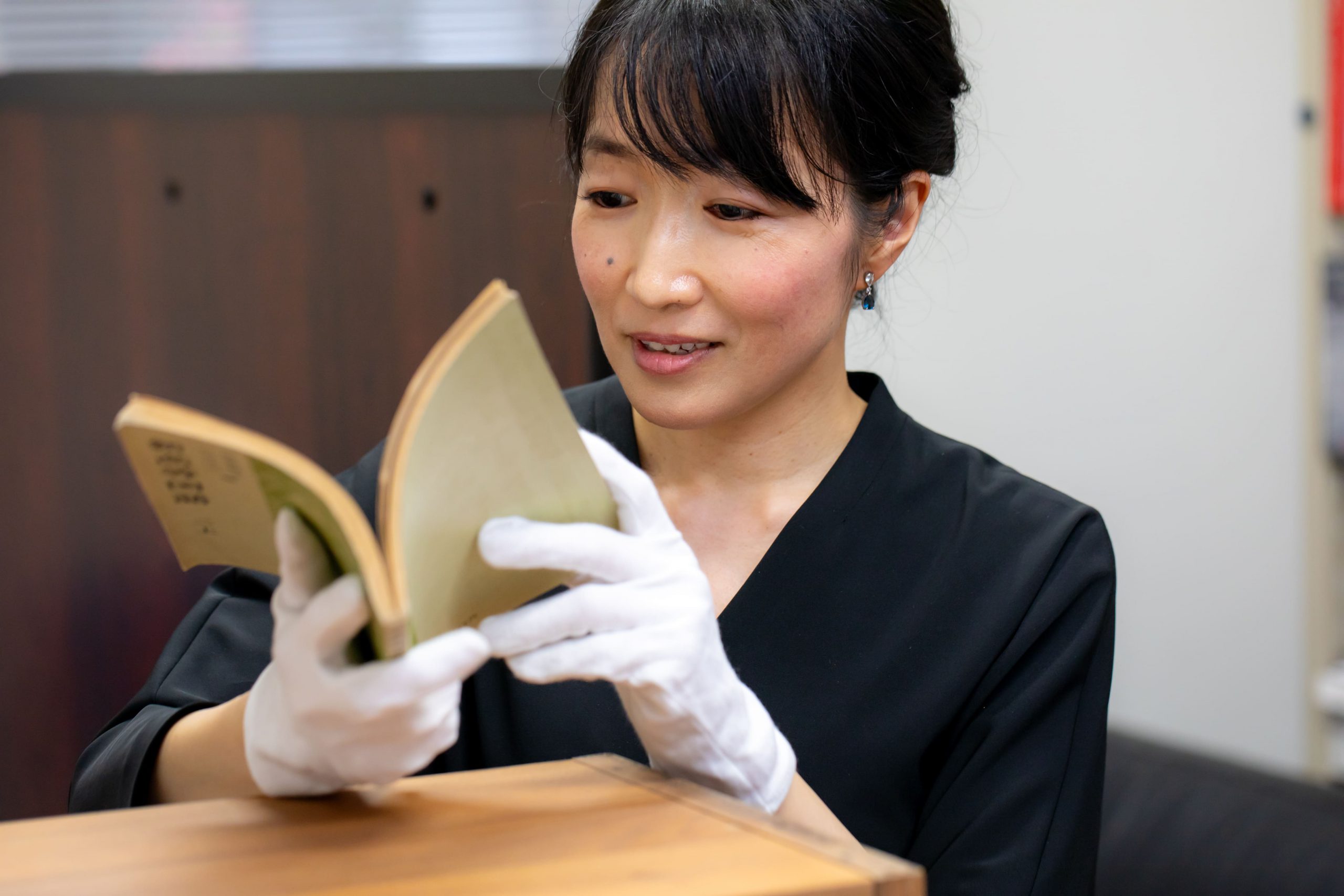

| By My Side | White Gloves Annotated screenplays and diaries are unique and invaluable resources. Some are purchased, while others are borrowed from museums or individuals with personal connections to the films. “Given the precious nature of these materials, utmost care is crucial when handling them. White gloves are indispensable when touching these documents. I’ve heard that Ozu had an assortment of white shirts for filming, and I have my collection of white gloves on my part (laughs).”  |

|---|---|

| Unchosen Path | Dr. Miyamoto answered that she would have wanted to be involved in producing a television series. “In my student days, I was involved in the planning and production of television programs. I felt excited and intrigued when my suggestions and feedback as a viewer were reflected in the final product, proving how even the smallest voice could have a meaningful impact on a program. I really wanted to create something in this way, working alongside so many other people.” |

Akiko Miyamoto

Associate Professor, Department of Japanese Language and Literature, Faculty of Culture and Representation, Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts. She holds a Ph.D. in Literature. After completing her postgraduate studies at Waseda University, she served as a teaching and research assistant at Waseda University, Assistant Professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and Assistant Professor at Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts before assuming her current position in 2021. She has been conducting research and interviews focusing mainly on handwritten materials by Yasujiro Ozu, such as shooting scripts and notebooks. The culmination of her work was the publication of Ozu Yasujiro taizen (translated title: The Complete Book of Ozu Yasujiro, written and edited by Kanji Matsuura & Akiko Miyamoto, Asahi Shimbun Publications Inc., March 2019). In March 2022, she co-authored and edited the revised and updated two-volume edition of Ozu Yasujiro: Hito to shigoto (translated title: Ozu Yasujiro: Life and Works – A Revised New Edition, written and edited by Kanji Matsuura & Akiko Miyamoto, originally written and published by Kazuo Inoue), a work that had been out of print and whose republication was highly anticipated. She also involves herself in planning and conducting film-related events.

Interview and original article: Izumi Kanchiku (team Pascal)

Photo: Maco Azuma